My Perspective on the Fate of the Donner Party

by Steve Dumolt

| The story

of the Donner-Reed Party making their way across the

country as part of the westward migration in 1846 and

culminating in their horrendous winter experience in the

Sierra Nevada Mountains, has probably been recounted and

analyzed by more experts and non-experts than any other

single aspect of the history of the West. I figured that

one more opinion/analysis wouldn't make a significant

difference, so here are my two cents. This is not a work

of scholarship by any stretch of the imagination. It's

just my un-referenced, un-footnoted, disorganized

analysis derived from source material, some of which is

noted below. I have assumed that the reader has a

reasonable knowledge of Western emigration in general

and the Donner Party in particular. After reading and viewing several treatments of the Donner Party story, including Ordeal By Hunger by George Stewart, Desperate Passage by Ethan Rarick, The Year of Decision: 1846 by Bernard DeVoto, and the film The Donner Party by Ric Burns, it dawned on me that the emigrants' misfortunes could be described using a simple (simplistic?) model. The members of the Donner Party found themselves in their predicament for three reasons: (1) they were ignorant, (2) they were reckless to the point of stupidity, (3) they were unlucky. The bottom line is that all three of these attributes had to be true for the name Donner to become infamous in the history of the American West. If any of the three had not been true, they would probably have arrived safely in California and the journey of the Donners, Reeds, and the others in the party would have been just one more virtually unknown footnote to the history of Western emigration. |

SETTING THE STAGE

The Donner Party wasn't really a distinct group

at the beginning of their cross-country migration in April

1846. George Donner, his brother Jacob, and James Reed, along

with their families and employees, had started together from

Springfield, Illinois but most of the others were later

additions. (The Graves family was the last to join, arriving

at the back of the train after the main party left Fort

Bridger and was approaching the Wasatch Mountains in what is today northeast Utah.) Of the nearly three

thousand emigrants headed up the valley of the Platte River

that year, some were headed for California and some for

Oregon. Most wagons were officially a member of one party or

another, but the composition of any one party varied as it

moved along due to the fact that many of the travelers joined

and left to accommodate difficulties on the trail as well as

individual traveling and social preferences. The Donner Party

had its official beginning at the Parting of the Ways in

western modern-day Wyoming. Up until then they were part of a

rather large group headed by William H. Russell (who was

eventually succeeded by Lilburn Boggs, former governor of

Missouri). At the Parting of the Ways most of the emigrants

who were going to Oregon or following the standard route to

California via Fort Hall (near Pocatello in modern-day Idaho)

took the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff and headed north. The

Donners, Reeds, and several other families headed south toward

Fort Bridger because they believed that a shortcut, promoted

by an individual named Lansford Hastings and popularly known

as Hastings Cutoff, passing south of the Great Salt Lake would

save them precious time and distance compared to the standard

route to California.

Hastings had even written an emigrants' guide to Oregon and

California that was well-known in the East. (Supposedly, the

Donners carried at least one copy with them.) It turns out

that when he wrote the guide he had never traveled the route

and had no idea whether or not it was passable with wagons.

The Donners were supposed to meet up with Hastings at Fort

Bridger but he had already left for California leading another

party of emigrants along his new route, so they had to either

try to follow as best as they could or backtrack and take the

Fort Hall route. (Hastings had arrived at Fort Bridger after

traveling his route for the first time, albeit backwards from

California on horseback.) Up to this point the Donner Party

was not much different from any other group to migrate west

that year. They started as a group in Independence, Missouri,

followed the Platte and Sweetwater Rivers, and traversed South

Pass. At the Parting of the Ways they went south like a few

other parties ahead of them. The only indication that trouble

might be brewing was a meeting with a former mountain man

named James Clyman at Fort Bernard, a small trading post back

up the trail a few miles east of Fort Laramie. I will expand

on this below but, suffice it to say, Clyman emphatically told

James Reed and the Donner brothers not to take their wagons on

the Hastings Cutoff. Obviously, the advice was ignored.

The Donner Party wasn't really a distinct group

at the beginning of their cross-country migration in April

1846. George Donner, his brother Jacob, and James Reed, along

with their families and employees, had started together from

Springfield, Illinois but most of the others were later

additions. (The Graves family was the last to join, arriving

at the back of the train after the main party left Fort

Bridger and was approaching the Wasatch Mountains in what is today northeast Utah.) Of the nearly three

thousand emigrants headed up the valley of the Platte River

that year, some were headed for California and some for

Oregon. Most wagons were officially a member of one party or

another, but the composition of any one party varied as it

moved along due to the fact that many of the travelers joined

and left to accommodate difficulties on the trail as well as

individual traveling and social preferences. The Donner Party

had its official beginning at the Parting of the Ways in

western modern-day Wyoming. Up until then they were part of a

rather large group headed by William H. Russell (who was

eventually succeeded by Lilburn Boggs, former governor of

Missouri). At the Parting of the Ways most of the emigrants

who were going to Oregon or following the standard route to

California via Fort Hall (near Pocatello in modern-day Idaho)

took the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff and headed north. The

Donners, Reeds, and several other families headed south toward

Fort Bridger because they believed that a shortcut, promoted

by an individual named Lansford Hastings and popularly known

as Hastings Cutoff, passing south of the Great Salt Lake would

save them precious time and distance compared to the standard

route to California.

Hastings had even written an emigrants' guide to Oregon and

California that was well-known in the East. (Supposedly, the

Donners carried at least one copy with them.) It turns out

that when he wrote the guide he had never traveled the route

and had no idea whether or not it was passable with wagons.

The Donners were supposed to meet up with Hastings at Fort

Bridger but he had already left for California leading another

party of emigrants along his new route, so they had to either

try to follow as best as they could or backtrack and take the

Fort Hall route. (Hastings had arrived at Fort Bridger after

traveling his route for the first time, albeit backwards from

California on horseback.) Up to this point the Donner Party

was not much different from any other group to migrate west

that year. They started as a group in Independence, Missouri,

followed the Platte and Sweetwater Rivers, and traversed South

Pass. At the Parting of the Ways they went south like a few

other parties ahead of them. The only indication that trouble

might be brewing was a meeting with a former mountain man

named James Clyman at Fort Bernard, a small trading post back

up the trail a few miles east of Fort Laramie. I will expand

on this below but, suffice it to say, Clyman emphatically told

James Reed and the Donner brothers not to take their wagons on

the Hastings Cutoff. Obviously, the advice was ignored.

It is my contention that there were three major contributors to the Donner tragedy: (1) like many of their fellow travelers they were ignorant with respect to many practical aspects of their journey, (2) unlike many of their fellow travelers they made recklessness decisions, and (3) they experienced an untimely occurrence of very bad luck. The most significant ramifications were exposed after they learned that Hastings would not be leading them personally but decided to follow the un-wagon-tested Hastings Cutoff anyway. Once they entered the Wasatch Mountains they were probably past the point-of-no-return.

The following sections contain descriptions of a few of the relevant situations and actions, and my analyses of their consequences.

THE IGNORANT,

Like most of the cross-country emigrants of the 1840s, the members of the Donner Party had no experience traveling in the western United States, especially in arid and mountainous areas. They had little or no experience surviving in wilderness situations. They were mostly businessmen/merchants (James Reed) and farmers (George and Jacob Donner) from the relatively settled parts of the eastern section of the continent. Some of the early migrations had relied on experienced guides for at least a portion of the trip, usually former mountain men like Caleb Greenwood and Thomas Fitzpatrick. By 1846 most parties figured they could carry guidebooks (like Lansford Hastings') and follow in the tracks of the wagons that had gone before them. Although disease, accidents, human conflicts, and natural phenomena took their toll, this strategy served most of them pretty well.

The

Donner Party more-or-less followed this same strategy.

Unfortunately, the guidebook they carried was Lansford

Hastings' and the wagon tracks they tried to follow were those

of the parties Hastings was leading back along his cutoff.

(These groups are often referred to collectively as the

Harlan-Young Party.)

The first serious problem arose almost immediately when they

tried to follow the same route Hastings had taken through

Weber Canyon into the Salt Lake Valley. Just after they

started they found a note from Hastings telling them that the

Weber Canyon route was virtually impassible for wagons and

that they would need to find another way, and if they sought

him out he would lead them by an easier and more direct way.

James Reed and two others rode ahead to track Hastings down, at which point he said he

wouldn't come back to lead them but, rather, took them to a nearby mountaintop

and pointed out a valley to the south that he thought might

work better. The Donners headed south and spent the better

part of two weeks hacking a new trail across the Wasatch into

the Salt Lake Valley. It is fairly sure thing that they lost a

lot of time creating a new road when there was supposed to be

one available to them already. The delay in getting a response

from Hastings plus the time it took to cut the new trail was

about sixteen days. It is not even clear that their

route-finding skills allowed them to choose the route Hastings

had pointed out. The particular way they went, entering the

Wasatch through East Canyon and exiting through Emigration

Canyon, may not have been the least difficult. It turns out

that the Donners' new trail was used the next year for the

first wave of Mormon emigration into the valley but after a

few years was replaced by an easier route immediately to the

south (followed by I-80 today). The Donner Party's

inexperience in road-building and route-finding is just one

example of the extra time and effort they required to overcome

some of the unexpected hurdles. If they had been able to save

even a week they probably could have made it over the crest of

the Sierra Nevada and part of the way to Sutter's Fort before

the big snow hit at the beginning of November. They might have

even been able to use the easier Roller Pass instead of Stephens

(now Donner) Pass to make the crossing. (Roller Pass, a mile or

two south of Stephens Pass, was higher but had a more gradual

approach and was first used by California-bound emigrants that

same year of 1846. Stephens Pass was first used by the

Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party, the first party to take wagons

across the Sierra Nevada in 1844. It is not clear if it was ever

called Stephens Pass, the name Donner Pass being adopted soon

after the Donner tragedy.)

The

Donner Party more-or-less followed this same strategy.

Unfortunately, the guidebook they carried was Lansford

Hastings' and the wagon tracks they tried to follow were those

of the parties Hastings was leading back along his cutoff.

(These groups are often referred to collectively as the

Harlan-Young Party.)

The first serious problem arose almost immediately when they

tried to follow the same route Hastings had taken through

Weber Canyon into the Salt Lake Valley. Just after they

started they found a note from Hastings telling them that the

Weber Canyon route was virtually impassible for wagons and

that they would need to find another way, and if they sought

him out he would lead them by an easier and more direct way.

James Reed and two others rode ahead to track Hastings down, at which point he said he

wouldn't come back to lead them but, rather, took them to a nearby mountaintop

and pointed out a valley to the south that he thought might

work better. The Donners headed south and spent the better

part of two weeks hacking a new trail across the Wasatch into

the Salt Lake Valley. It is fairly sure thing that they lost a

lot of time creating a new road when there was supposed to be

one available to them already. The delay in getting a response

from Hastings plus the time it took to cut the new trail was

about sixteen days. It is not even clear that their

route-finding skills allowed them to choose the route Hastings

had pointed out. The particular way they went, entering the

Wasatch through East Canyon and exiting through Emigration

Canyon, may not have been the least difficult. It turns out

that the Donners' new trail was used the next year for the

first wave of Mormon emigration into the valley but after a

few years was replaced by an easier route immediately to the

south (followed by I-80 today). The Donner Party's

inexperience in road-building and route-finding is just one

example of the extra time and effort they required to overcome

some of the unexpected hurdles. If they had been able to save

even a week they probably could have made it over the crest of

the Sierra Nevada and part of the way to Sutter's Fort before

the big snow hit at the beginning of November. They might have

even been able to use the easier Roller Pass instead of Stephens

(now Donner) Pass to make the crossing. (Roller Pass, a mile or

two south of Stephens Pass, was higher but had a more gradual

approach and was first used by California-bound emigrants that

same year of 1846. Stephens Pass was first used by the

Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party, the first party to take wagons

across the Sierra Nevada in 1844. It is not clear if it was ever

called Stephens Pass, the name Donner Pass being adopted soon

after the Donner tragedy.)

Their inexperience and lack of wilderness skills had a more significant consequence during the time the party was actually trapped at the foot of Stephens Pass from early November 1846, when the pass was closed by snow, to mid-February 1847, when the first relief party reached them. Their inability to build adequate shelter or find sufficient food created a situation which certainly contributed to the high death toll. Whatever domesticated animals they had left were quickly dispatched. They were able to kill a few animals in the woods early on before the snow became too deep and most of the game had migrated to lower elevations for the winter. There were fish in the lake but all their fishing methods proved ineffective. By the time winter hit them in earnest they were reduced to boiling buffalo hides to extract whatever nutrients they could.

Although the members of the Donner Party suffered greatly in the mountains, it was by no means impossible to survive the winter. There were Indians in the vicinity who, by virtue of their familiarity with the region, had developed adequate coping mechanisms. In addition, two years earlier the Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party had to leave a few of their wagons on the east side of the pass and one of their group managed to stay with them for a portion of the winter. In fact, one of the Donner Party families, the Breens, stayed in the cabin built to shelter that individual (Moses Schallenberger).

One more situation that needs to be mentioned with respect to lack of wilderness skills is that of the snowshoe party that left the camp on the lake on December 16, made its way across the pass and down to Johnson's Ranch a month later. Fifteen individuals started the trek wearing homemade snowshoes, ten men and five women. Eight of the men died on the way; two men and all five women survived. The fact that any of them made it was a miracle. Only by eating the flesh of their dead companions and receiving help at critical times from friendly Indians did one of them (William Eddy) manage to make it to Johnson's Ranch to ask for help. The bravery and perseverance of the members of the party was remarkable and they provided evidence that people were alive back over the pass, but they did so at a cost of over 50% of their group.

THE RECKLESS,

In addition to being greenhorns, the members of the Donner Party made some rather foolish decisions which contributed to their eventual tragic situation. Some of these might be justified if evaluated in the perspective of the time and place on the California Trail in 1846, rather than judging them with 20/20 hindsight over 150 years later. Others, however, are difficult to explain even in that light.

In

my opinion, the most damaging decision was to take Hastings

Cutoff. James Reed, the de

facto leader of the Donner Party, had probably made

up his mind to take the cutoff even before they left

Springfield, Illinois. While it may have appeared to be a good

idea at the time, a chance meeting on the Platte River should

have changed his mind. As the wagons approached Fort Laramie,

in southeast Wyoming, they came upon a small trading post

eight miles to the east called Fort Bernard. Here James Reed

encountered a former mountain man named James Clyman. Clyman

had a history dating back to the early 1820s. He had worked in

the fur trade and traveled all over the West. He was with

Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick when they made the "latest" discovery of South Pass in 1824 and was

also one of the earliest explorers of the Great Salt Lake.

He had just accompanied Lansford Hastings back from

California along Hastings Cutoff so he had an excellent

opportunity to evaluate the suitability of the route for

wagon travel. Moreover, he and Reed had known each other

fourteen years earlier when they served in the same Illinois

militia company during the Black Hawk War. (One of their

fellow militiamen was a guy named Abraham Lincoln.) When he

found out that Reed was planning to take Hastings' route,

Clyman told him (and the Donner brothers, who were part of

the conversation) in no uncertain terms that it was

unsuitable for wagons and that they should follow the

standard route by way of Fort Hall. Reed responded by saying

that the Hastings route was shorter and he was going to take

it regardless. In deciding to follow the advice of a

stranger who had written a guidebook instead of listening to

a bona fide mountain man who had been over the route and who

he knew personally, Reed demonstrated that he was not immune

to folly. (Maybe cognitive dissonance reared its ugly head

and Reed exhibited the standard response - he went with his

emotions rather than the evidence before him.)

In

my opinion, the most damaging decision was to take Hastings

Cutoff. James Reed, the de

facto leader of the Donner Party, had probably made

up his mind to take the cutoff even before they left

Springfield, Illinois. While it may have appeared to be a good

idea at the time, a chance meeting on the Platte River should

have changed his mind. As the wagons approached Fort Laramie,

in southeast Wyoming, they came upon a small trading post

eight miles to the east called Fort Bernard. Here James Reed

encountered a former mountain man named James Clyman. Clyman

had a history dating back to the early 1820s. He had worked in

the fur trade and traveled all over the West. He was with

Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick when they made the "latest" discovery of South Pass in 1824 and was

also one of the earliest explorers of the Great Salt Lake.

He had just accompanied Lansford Hastings back from

California along Hastings Cutoff so he had an excellent

opportunity to evaluate the suitability of the route for

wagon travel. Moreover, he and Reed had known each other

fourteen years earlier when they served in the same Illinois

militia company during the Black Hawk War. (One of their

fellow militiamen was a guy named Abraham Lincoln.) When he

found out that Reed was planning to take Hastings' route,

Clyman told him (and the Donner brothers, who were part of

the conversation) in no uncertain terms that it was

unsuitable for wagons and that they should follow the

standard route by way of Fort Hall. Reed responded by saying

that the Hastings route was shorter and he was going to take

it regardless. In deciding to follow the advice of a

stranger who had written a guidebook instead of listening to

a bona fide mountain man who had been over the route and who

he knew personally, Reed demonstrated that he was not immune

to folly. (Maybe cognitive dissonance reared its ugly head

and Reed exhibited the standard response - he went with his

emotions rather than the evidence before him.)

Even if Hastings' Cutoff had been an easily passable road, by leaving the standard route the Donner Party created a problem - or at least a potential problem. They significantly reduced the potential availability of assistance from forts, trading posts, and fellow emigrants. Between Fort Bridger and Johnson's Ranch there was little or no potential for assistance; they were on their own. The fact that they were the last party on the trail made the situation even more perilous. Maybe some of their difficulties the rest of the way could have been mitigated if aid had been available.

The Hastings route wasn't impossible; the two or three parties just ahead of the Donner Party, led by Lansford Hastings himself, made it across the desert, over the Sierra Nevada, and into California safely. As mentioned above, when the Donners tried to follow the Hastings group through Weber Canon they found a note from Hastings saying that they should find another route. Here they made a decision that looks worse in hindsight but obviously didn't at the time. It should have been apparent that Hastings didn't know where his route went. They had also been told at Fort Bridger that the road was level with plenty of grass. This was not true; Jim Bridger had given them overly optimistic advice, even though he had no idea about the condition of the cutoff, in hopes that it would keep him from losing business due to the popularity of the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff up north, which bypassed his fort. (Unknown to the Donners, there was a letter left at Fort Bridger from an emigrant named Edwin Bryant advising them not to take wagons on the cutoff. They never got the letter.) At the time, considering the false information they had been given, warning sirens should have been going off in their heads. Rather than retrace their steps and go back to the Fort Hall route, and after some discussion, they decided to follow Hastings' advice and tried to blaze the road further south, with the now-historic consequences. To be fair to both Hastings and the Donner Party, a couple of points should be made. There are some sources that indicate that the route down Weber Canyon was not part of the Hastings Cutoff and that the decision to go that way was not made by Hastings. He was some forty miles in the rear at the time and not available for consultation. The Harlan-Young group turned right after exiting Echo Canyon and headed straight for Weber Canyon. The Donner Party effectively made the right turn but then headed west into East Canyon. Taking the route that eventually became the principal road into the Salt Lake Valley (along today's I-80) would have required turning left after exiting Echo Canyon. The second point is that although the Donner Party decided to forge ahead despite the knowledge that some of their information was incorrect, they may have thought they were beyond the point of no return. They may have judged that the time it would have taken to backtrack and follow the standard trail may have been more than the time they estimated it was going to take for them to go forward on the cutoff.

Before I leave this section I need to mention the Pioneer Palace Car. I'm not sure if it should be in this section or "The Ignorant", but it does deserve a sentence or two. The Reed family had a custom-built wagon that their daughter, Virginia, named the Pioneer Palace Car. It was an oversized wagon, pulled by four yoke of oxen, with two levels, spring seats, built-in beds, and a stove. The Pioneer Palace Car was completely inappropriate for a journey such as the one the emigrants would take and eventually had to be abandoned along the way.

AND THE UNLUCKY.

Besides being ignorant and reckless, the Donner Party was also very unlucky. The most obvious instance of bad luck occurred as the lead wagons were approaching the Sierra Nevada mountains in the last week of October, when snow closed the pass before they could get over. In a normal year the pass was open until late in November. This year, however, the snow began falling on October 31st. Despite all their problems and delays, if the snow had held off for a week or two the Donners could have gotten over the pass and been on their way to Johnson's Ranch and Sutter's Fort.

In

previous years, emigrant parties had reached the Sierra Nevada

much later than the Donner Party did in 1846 and were still

able to cross. Two years earlier, in 1844, the

Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party had crossed the pass on

November 25th. They were the first party to take wagons over

the Sierra Nevada but did so with two feet of snow on the

ground. Although they made it over the pass, some members of

their party were caught by more snow on the descent down the

west side and had to be rescued. The next year a party on

horseback crossed the pass in early December. The first part

of the group, led by John C. Fremont, crossed the pass on

December 5th. The rest of the group crossed a few days later.

In a bit of irony, one of the members of the second group was

Lansford Hastings.

In

previous years, emigrant parties had reached the Sierra Nevada

much later than the Donner Party did in 1846 and were still

able to cross. Two years earlier, in 1844, the

Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party had crossed the pass on

November 25th. They were the first party to take wagons over

the Sierra Nevada but did so with two feet of snow on the

ground. Although they made it over the pass, some members of

their party were caught by more snow on the descent down the

west side and had to be rescued. The next year a party on

horseback crossed the pass in early December. The first part

of the group, led by John C. Fremont, crossed the pass on

December 5th. The rest of the group crossed a few days later.

In a bit of irony, one of the members of the second group was

Lansford Hastings.

One more aspect of luck that should be included was mentioned earlier, when the Harlan-Young group took a (possibly) wrong turn in the Wasatch and had to make their way down Weber Canyon. If they had gone the way Hastings had (supposedly) intended, the new road would have been ready for the Donner Party or at least well on the way to completion. The time saved might have made the difference between spending the winter in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and spending it in the San Francisco (Yerba Buena) Bay Area.

WRAP-UP

The Donner Party's fate was sealed because of three attributes: they were ignorant, they were reckless, and they were unlucky. If any of these did not apply, the members of the party would have made it to California like about 1500 other emigrants in 1846. If they had not been unlucky and been trapped by the early snows they probably would have made it. If they had not been reckless and taken the Hastings Cutoff instead of the Fort Hall route, they probably would have made it. Lastly, if they had not been greenhorns they may have been able to save (or not lose) enough time to make it over the pass in time. Even if they had been trapped, with wilderness knowledge and skills they could have survived the winter with much less suffering and death, like the many mountain men and local indigenous people who did so on a routine basis.

The Donner Party wasn't really a distinct group

at the beginning of their cross-country migration in April

1846. George Donner, his brother Jacob, and James Reed, along

with their families and employees, had started together from

Springfield, Illinois but most of the others were later

additions. (The Graves family was the last to join, arriving

at the back of the train after the main party left Fort

Bridger and was approaching the Wasatch Mountains in what is today northeast Utah.) Of the nearly three

thousand emigrants headed up the valley of the Platte River

that year, some were headed for California and some for

Oregon. Most wagons were officially a member of one party or

another, but the composition of any one party varied as it

moved along due to the fact that many of the travelers joined

and left to accommodate difficulties on the trail as well as

individual traveling and social preferences. The Donner Party

had its official beginning at the Parting of the Ways in

western modern-day Wyoming. Up until then they were part of a

rather large group headed by William H. Russell (who was

eventually succeeded by Lilburn Boggs, former governor of

Missouri). At the Parting of the Ways most of the emigrants

who were going to Oregon or following the standard route to

California via Fort Hall (near Pocatello in modern-day Idaho)

took the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff and headed north. The

Donners, Reeds, and several other families headed south toward

Fort Bridger because they believed that a shortcut, promoted

by an individual named Lansford Hastings and popularly known

as Hastings Cutoff, passing south of the Great Salt Lake would

save them precious time and distance compared to the standard

route to California.

Hastings had even written an emigrants' guide to Oregon and

California that was well-known in the East. (Supposedly, the

Donners carried at least one copy with them.) It turns out

that when he wrote the guide he had never traveled the route

and had no idea whether or not it was passable with wagons.

The Donners were supposed to meet up with Hastings at Fort

Bridger but he had already left for California leading another

party of emigrants along his new route, so they had to either

try to follow as best as they could or backtrack and take the

Fort Hall route. (Hastings had arrived at Fort Bridger after

traveling his route for the first time, albeit backwards from

California on horseback.) Up to this point the Donner Party

was not much different from any other group to migrate west

that year. They started as a group in Independence, Missouri,

followed the Platte and Sweetwater Rivers, and traversed South

Pass. At the Parting of the Ways they went south like a few

other parties ahead of them. The only indication that trouble

might be brewing was a meeting with a former mountain man

named James Clyman at Fort Bernard, a small trading post back

up the trail a few miles east of Fort Laramie. I will expand

on this below but, suffice it to say, Clyman emphatically told

James Reed and the Donner brothers not to take their wagons on

the Hastings Cutoff. Obviously, the advice was ignored.

The Donner Party wasn't really a distinct group

at the beginning of their cross-country migration in April

1846. George Donner, his brother Jacob, and James Reed, along

with their families and employees, had started together from

Springfield, Illinois but most of the others were later

additions. (The Graves family was the last to join, arriving

at the back of the train after the main party left Fort

Bridger and was approaching the Wasatch Mountains in what is today northeast Utah.) Of the nearly three

thousand emigrants headed up the valley of the Platte River

that year, some were headed for California and some for

Oregon. Most wagons were officially a member of one party or

another, but the composition of any one party varied as it

moved along due to the fact that many of the travelers joined

and left to accommodate difficulties on the trail as well as

individual traveling and social preferences. The Donner Party

had its official beginning at the Parting of the Ways in

western modern-day Wyoming. Up until then they were part of a

rather large group headed by William H. Russell (who was

eventually succeeded by Lilburn Boggs, former governor of

Missouri). At the Parting of the Ways most of the emigrants

who were going to Oregon or following the standard route to

California via Fort Hall (near Pocatello in modern-day Idaho)

took the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff and headed north. The

Donners, Reeds, and several other families headed south toward

Fort Bridger because they believed that a shortcut, promoted

by an individual named Lansford Hastings and popularly known

as Hastings Cutoff, passing south of the Great Salt Lake would

save them precious time and distance compared to the standard

route to California.

Hastings had even written an emigrants' guide to Oregon and

California that was well-known in the East. (Supposedly, the

Donners carried at least one copy with them.) It turns out

that when he wrote the guide he had never traveled the route

and had no idea whether or not it was passable with wagons.

The Donners were supposed to meet up with Hastings at Fort

Bridger but he had already left for California leading another

party of emigrants along his new route, so they had to either

try to follow as best as they could or backtrack and take the

Fort Hall route. (Hastings had arrived at Fort Bridger after

traveling his route for the first time, albeit backwards from

California on horseback.) Up to this point the Donner Party

was not much different from any other group to migrate west

that year. They started as a group in Independence, Missouri,

followed the Platte and Sweetwater Rivers, and traversed South

Pass. At the Parting of the Ways they went south like a few

other parties ahead of them. The only indication that trouble

might be brewing was a meeting with a former mountain man

named James Clyman at Fort Bernard, a small trading post back

up the trail a few miles east of Fort Laramie. I will expand

on this below but, suffice it to say, Clyman emphatically told

James Reed and the Donner brothers not to take their wagons on

the Hastings Cutoff. Obviously, the advice was ignored.It is my contention that there were three major contributors to the Donner tragedy: (1) like many of their fellow travelers they were ignorant with respect to many practical aspects of their journey, (2) unlike many of their fellow travelers they made recklessness decisions, and (3) they experienced an untimely occurrence of very bad luck. The most significant ramifications were exposed after they learned that Hastings would not be leading them personally but decided to follow the un-wagon-tested Hastings Cutoff anyway. Once they entered the Wasatch Mountains they were probably past the point-of-no-return.

The following sections contain descriptions of a few of the relevant situations and actions, and my analyses of their consequences.

THE IGNORANT,

Like most of the cross-country emigrants of the 1840s, the members of the Donner Party had no experience traveling in the western United States, especially in arid and mountainous areas. They had little or no experience surviving in wilderness situations. They were mostly businessmen/merchants (James Reed) and farmers (George and Jacob Donner) from the relatively settled parts of the eastern section of the continent. Some of the early migrations had relied on experienced guides for at least a portion of the trip, usually former mountain men like Caleb Greenwood and Thomas Fitzpatrick. By 1846 most parties figured they could carry guidebooks (like Lansford Hastings') and follow in the tracks of the wagons that had gone before them. Although disease, accidents, human conflicts, and natural phenomena took their toll, this strategy served most of them pretty well.

The

Donner Party more-or-less followed this same strategy.

Unfortunately, the guidebook they carried was Lansford

Hastings' and the wagon tracks they tried to follow were those

of the parties Hastings was leading back along his cutoff.

(These groups are often referred to collectively as the

Harlan-Young Party.)

The first serious problem arose almost immediately when they

tried to follow the same route Hastings had taken through

Weber Canyon into the Salt Lake Valley. Just after they

started they found a note from Hastings telling them that the

Weber Canyon route was virtually impassible for wagons and

that they would need to find another way, and if they sought

him out he would lead them by an easier and more direct way.

James Reed and two others rode ahead to track Hastings down, at which point he said he

wouldn't come back to lead them but, rather, took them to a nearby mountaintop

and pointed out a valley to the south that he thought might

work better. The Donners headed south and spent the better

part of two weeks hacking a new trail across the Wasatch into

the Salt Lake Valley. It is fairly sure thing that they lost a

lot of time creating a new road when there was supposed to be

one available to them already. The delay in getting a response

from Hastings plus the time it took to cut the new trail was

about sixteen days. It is not even clear that their

route-finding skills allowed them to choose the route Hastings

had pointed out. The particular way they went, entering the

Wasatch through East Canyon and exiting through Emigration

Canyon, may not have been the least difficult. It turns out

that the Donners' new trail was used the next year for the

first wave of Mormon emigration into the valley but after a

few years was replaced by an easier route immediately to the

south (followed by I-80 today). The Donner Party's

inexperience in road-building and route-finding is just one

example of the extra time and effort they required to overcome

some of the unexpected hurdles. If they had been able to save

even a week they probably could have made it over the crest of

the Sierra Nevada and part of the way to Sutter's Fort before

the big snow hit at the beginning of November. They might have

even been able to use the easier Roller Pass instead of Stephens

(now Donner) Pass to make the crossing. (Roller Pass, a mile or

two south of Stephens Pass, was higher but had a more gradual

approach and was first used by California-bound emigrants that

same year of 1846. Stephens Pass was first used by the

Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party, the first party to take wagons

across the Sierra Nevada in 1844. It is not clear if it was ever

called Stephens Pass, the name Donner Pass being adopted soon

after the Donner tragedy.)

The

Donner Party more-or-less followed this same strategy.

Unfortunately, the guidebook they carried was Lansford

Hastings' and the wagon tracks they tried to follow were those

of the parties Hastings was leading back along his cutoff.

(These groups are often referred to collectively as the

Harlan-Young Party.)

The first serious problem arose almost immediately when they

tried to follow the same route Hastings had taken through

Weber Canyon into the Salt Lake Valley. Just after they

started they found a note from Hastings telling them that the

Weber Canyon route was virtually impassible for wagons and

that they would need to find another way, and if they sought

him out he would lead them by an easier and more direct way.

James Reed and two others rode ahead to track Hastings down, at which point he said he

wouldn't come back to lead them but, rather, took them to a nearby mountaintop

and pointed out a valley to the south that he thought might

work better. The Donners headed south and spent the better

part of two weeks hacking a new trail across the Wasatch into

the Salt Lake Valley. It is fairly sure thing that they lost a

lot of time creating a new road when there was supposed to be

one available to them already. The delay in getting a response

from Hastings plus the time it took to cut the new trail was

about sixteen days. It is not even clear that their

route-finding skills allowed them to choose the route Hastings

had pointed out. The particular way they went, entering the

Wasatch through East Canyon and exiting through Emigration

Canyon, may not have been the least difficult. It turns out

that the Donners' new trail was used the next year for the

first wave of Mormon emigration into the valley but after a

few years was replaced by an easier route immediately to the

south (followed by I-80 today). The Donner Party's

inexperience in road-building and route-finding is just one

example of the extra time and effort they required to overcome

some of the unexpected hurdles. If they had been able to save

even a week they probably could have made it over the crest of

the Sierra Nevada and part of the way to Sutter's Fort before

the big snow hit at the beginning of November. They might have

even been able to use the easier Roller Pass instead of Stephens

(now Donner) Pass to make the crossing. (Roller Pass, a mile or

two south of Stephens Pass, was higher but had a more gradual

approach and was first used by California-bound emigrants that

same year of 1846. Stephens Pass was first used by the

Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party, the first party to take wagons

across the Sierra Nevada in 1844. It is not clear if it was ever

called Stephens Pass, the name Donner Pass being adopted soon

after the Donner tragedy.)Their inexperience and lack of wilderness skills had a more significant consequence during the time the party was actually trapped at the foot of Stephens Pass from early November 1846, when the pass was closed by snow, to mid-February 1847, when the first relief party reached them. Their inability to build adequate shelter or find sufficient food created a situation which certainly contributed to the high death toll. Whatever domesticated animals they had left were quickly dispatched. They were able to kill a few animals in the woods early on before the snow became too deep and most of the game had migrated to lower elevations for the winter. There were fish in the lake but all their fishing methods proved ineffective. By the time winter hit them in earnest they were reduced to boiling buffalo hides to extract whatever nutrients they could.

Although the members of the Donner Party suffered greatly in the mountains, it was by no means impossible to survive the winter. There were Indians in the vicinity who, by virtue of their familiarity with the region, had developed adequate coping mechanisms. In addition, two years earlier the Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party had to leave a few of their wagons on the east side of the pass and one of their group managed to stay with them for a portion of the winter. In fact, one of the Donner Party families, the Breens, stayed in the cabin built to shelter that individual (Moses Schallenberger).

One more situation that needs to be mentioned with respect to lack of wilderness skills is that of the snowshoe party that left the camp on the lake on December 16, made its way across the pass and down to Johnson's Ranch a month later. Fifteen individuals started the trek wearing homemade snowshoes, ten men and five women. Eight of the men died on the way; two men and all five women survived. The fact that any of them made it was a miracle. Only by eating the flesh of their dead companions and receiving help at critical times from friendly Indians did one of them (William Eddy) manage to make it to Johnson's Ranch to ask for help. The bravery and perseverance of the members of the party was remarkable and they provided evidence that people were alive back over the pass, but they did so at a cost of over 50% of their group.

THE RECKLESS,

In addition to being greenhorns, the members of the Donner Party made some rather foolish decisions which contributed to their eventual tragic situation. Some of these might be justified if evaluated in the perspective of the time and place on the California Trail in 1846, rather than judging them with 20/20 hindsight over 150 years later. Others, however, are difficult to explain even in that light.

In

my opinion, the most damaging decision was to take Hastings

Cutoff. James Reed, the de

facto leader of the Donner Party, had probably made

up his mind to take the cutoff even before they left

Springfield, Illinois. While it may have appeared to be a good

idea at the time, a chance meeting on the Platte River should

have changed his mind. As the wagons approached Fort Laramie,

in southeast Wyoming, they came upon a small trading post

eight miles to the east called Fort Bernard. Here James Reed

encountered a former mountain man named James Clyman. Clyman

had a history dating back to the early 1820s. He had worked in

the fur trade and traveled all over the West. He was with

Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick when they made the "latest" discovery of South Pass in 1824 and was

also one of the earliest explorers of the Great Salt Lake.

He had just accompanied Lansford Hastings back from

California along Hastings Cutoff so he had an excellent

opportunity to evaluate the suitability of the route for

wagon travel. Moreover, he and Reed had known each other

fourteen years earlier when they served in the same Illinois

militia company during the Black Hawk War. (One of their

fellow militiamen was a guy named Abraham Lincoln.) When he

found out that Reed was planning to take Hastings' route,

Clyman told him (and the Donner brothers, who were part of

the conversation) in no uncertain terms that it was

unsuitable for wagons and that they should follow the

standard route by way of Fort Hall. Reed responded by saying

that the Hastings route was shorter and he was going to take

it regardless. In deciding to follow the advice of a

stranger who had written a guidebook instead of listening to

a bona fide mountain man who had been over the route and who

he knew personally, Reed demonstrated that he was not immune

to folly. (Maybe cognitive dissonance reared its ugly head

and Reed exhibited the standard response - he went with his

emotions rather than the evidence before him.)

In

my opinion, the most damaging decision was to take Hastings

Cutoff. James Reed, the de

facto leader of the Donner Party, had probably made

up his mind to take the cutoff even before they left

Springfield, Illinois. While it may have appeared to be a good

idea at the time, a chance meeting on the Platte River should

have changed his mind. As the wagons approached Fort Laramie,

in southeast Wyoming, they came upon a small trading post

eight miles to the east called Fort Bernard. Here James Reed

encountered a former mountain man named James Clyman. Clyman

had a history dating back to the early 1820s. He had worked in

the fur trade and traveled all over the West. He was with

Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick when they made the "latest" discovery of South Pass in 1824 and was

also one of the earliest explorers of the Great Salt Lake.

He had just accompanied Lansford Hastings back from

California along Hastings Cutoff so he had an excellent

opportunity to evaluate the suitability of the route for

wagon travel. Moreover, he and Reed had known each other

fourteen years earlier when they served in the same Illinois

militia company during the Black Hawk War. (One of their

fellow militiamen was a guy named Abraham Lincoln.) When he

found out that Reed was planning to take Hastings' route,

Clyman told him (and the Donner brothers, who were part of

the conversation) in no uncertain terms that it was

unsuitable for wagons and that they should follow the

standard route by way of Fort Hall. Reed responded by saying

that the Hastings route was shorter and he was going to take

it regardless. In deciding to follow the advice of a

stranger who had written a guidebook instead of listening to

a bona fide mountain man who had been over the route and who

he knew personally, Reed demonstrated that he was not immune

to folly. (Maybe cognitive dissonance reared its ugly head

and Reed exhibited the standard response - he went with his

emotions rather than the evidence before him.)Even if Hastings' Cutoff had been an easily passable road, by leaving the standard route the Donner Party created a problem - or at least a potential problem. They significantly reduced the potential availability of assistance from forts, trading posts, and fellow emigrants. Between Fort Bridger and Johnson's Ranch there was little or no potential for assistance; they were on their own. The fact that they were the last party on the trail made the situation even more perilous. Maybe some of their difficulties the rest of the way could have been mitigated if aid had been available.

The Hastings route wasn't impossible; the two or three parties just ahead of the Donner Party, led by Lansford Hastings himself, made it across the desert, over the Sierra Nevada, and into California safely. As mentioned above, when the Donners tried to follow the Hastings group through Weber Canon they found a note from Hastings saying that they should find another route. Here they made a decision that looks worse in hindsight but obviously didn't at the time. It should have been apparent that Hastings didn't know where his route went. They had also been told at Fort Bridger that the road was level with plenty of grass. This was not true; Jim Bridger had given them overly optimistic advice, even though he had no idea about the condition of the cutoff, in hopes that it would keep him from losing business due to the popularity of the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff up north, which bypassed his fort. (Unknown to the Donners, there was a letter left at Fort Bridger from an emigrant named Edwin Bryant advising them not to take wagons on the cutoff. They never got the letter.) At the time, considering the false information they had been given, warning sirens should have been going off in their heads. Rather than retrace their steps and go back to the Fort Hall route, and after some discussion, they decided to follow Hastings' advice and tried to blaze the road further south, with the now-historic consequences. To be fair to both Hastings and the Donner Party, a couple of points should be made. There are some sources that indicate that the route down Weber Canyon was not part of the Hastings Cutoff and that the decision to go that way was not made by Hastings. He was some forty miles in the rear at the time and not available for consultation. The Harlan-Young group turned right after exiting Echo Canyon and headed straight for Weber Canyon. The Donner Party effectively made the right turn but then headed west into East Canyon. Taking the route that eventually became the principal road into the Salt Lake Valley (along today's I-80) would have required turning left after exiting Echo Canyon. The second point is that although the Donner Party decided to forge ahead despite the knowledge that some of their information was incorrect, they may have thought they were beyond the point of no return. They may have judged that the time it would have taken to backtrack and follow the standard trail may have been more than the time they estimated it was going to take for them to go forward on the cutoff.

Before I leave this section I need to mention the Pioneer Palace Car. I'm not sure if it should be in this section or "The Ignorant", but it does deserve a sentence or two. The Reed family had a custom-built wagon that their daughter, Virginia, named the Pioneer Palace Car. It was an oversized wagon, pulled by four yoke of oxen, with two levels, spring seats, built-in beds, and a stove. The Pioneer Palace Car was completely inappropriate for a journey such as the one the emigrants would take and eventually had to be abandoned along the way.

AND THE UNLUCKY.

Besides being ignorant and reckless, the Donner Party was also very unlucky. The most obvious instance of bad luck occurred as the lead wagons were approaching the Sierra Nevada mountains in the last week of October, when snow closed the pass before they could get over. In a normal year the pass was open until late in November. This year, however, the snow began falling on October 31st. Despite all their problems and delays, if the snow had held off for a week or two the Donners could have gotten over the pass and been on their way to Johnson's Ranch and Sutter's Fort.

In

previous years, emigrant parties had reached the Sierra Nevada

much later than the Donner Party did in 1846 and were still

able to cross. Two years earlier, in 1844, the

Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party had crossed the pass on

November 25th. They were the first party to take wagons over

the Sierra Nevada but did so with two feet of snow on the

ground. Although they made it over the pass, some members of

their party were caught by more snow on the descent down the

west side and had to be rescued. The next year a party on

horseback crossed the pass in early December. The first part

of the group, led by John C. Fremont, crossed the pass on

December 5th. The rest of the group crossed a few days later.

In a bit of irony, one of the members of the second group was

Lansford Hastings.

In

previous years, emigrant parties had reached the Sierra Nevada

much later than the Donner Party did in 1846 and were still

able to cross. Two years earlier, in 1844, the

Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party had crossed the pass on

November 25th. They were the first party to take wagons over

the Sierra Nevada but did so with two feet of snow on the

ground. Although they made it over the pass, some members of

their party were caught by more snow on the descent down the

west side and had to be rescued. The next year a party on

horseback crossed the pass in early December. The first part

of the group, led by John C. Fremont, crossed the pass on

December 5th. The rest of the group crossed a few days later.

In a bit of irony, one of the members of the second group was

Lansford Hastings.One more aspect of luck that should be included was mentioned earlier, when the Harlan-Young group took a (possibly) wrong turn in the Wasatch and had to make their way down Weber Canyon. If they had gone the way Hastings had (supposedly) intended, the new road would have been ready for the Donner Party or at least well on the way to completion. The time saved might have made the difference between spending the winter in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and spending it in the San Francisco (Yerba Buena) Bay Area.

WRAP-UP

The Donner Party's fate was sealed because of three attributes: they were ignorant, they were reckless, and they were unlucky. If any of these did not apply, the members of the party would have made it to California like about 1500 other emigrants in 1846. If they had not been unlucky and been trapped by the early snows they probably would have made it. If they had not been reckless and taken the Hastings Cutoff instead of the Fort Hall route, they probably would have made it. Lastly, if they had not been greenhorns they may have been able to save (or not lose) enough time to make it over the pass in time. Even if they had been trapped, with wilderness knowledge and skills they could have survived the winter with much less suffering and death, like the many mountain men and local indigenous people who did so on a routine basis.

| PARTIAL LIST

OF SOURCE MATERIAL BOOKS

DeVoto, Bernard. The Year of Decision: 1846 King, Joseph A. Winter of Entrapment: A New Look at the Donner Party McLaughlin, Mark. The Donner Party: Weathering the Storm Rarick, Ethan. Desperate Passage Stewart, George R. Ordeal By Hunger Unruh, John R., Jr. The Plains Across VIDEO The Donner Party, a film by Ric Burns INTERNET Various web sites, especially: The Donner Party Diary New Light on the Donner Party |

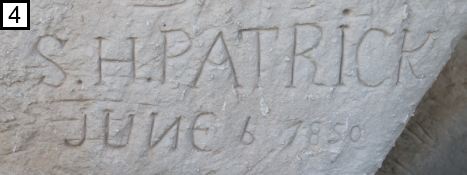

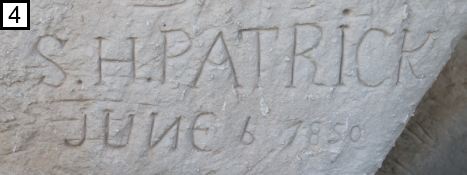

PHOTOS

|

||

Steve may be contacted at:

Last Update: 11

March 2023